America��s

Arsenal of democracy Angela Fu

Kevin Starr was born on September 3, 1940. He served in the U.S.

Army in West Germany

during the 1960s and attended the University

of San Francisco and Harvard

University.

Starr was California State Librarian from 1994 to 2004 and then received a National

Humanities Medal in 2006. He is currently a professor at the University

of Southern California but has taught or lectured at numerous universities

throughout California.

World War II changed the United

States as a whole, pulling the nation out of the Great Depression and turning

it into a world power, but the war had an especially great impact on the state

of California, which Kevin Starr makes a case for in Embattled Dreams, California in War and Peace 1940 �V 1950.

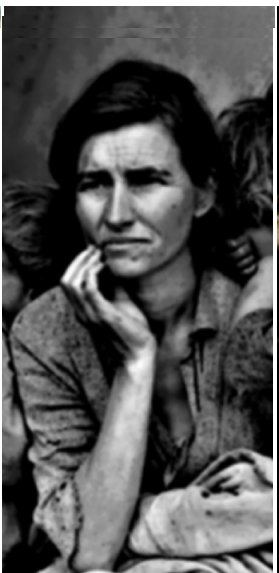

An influx of displaced Okies, Japanese, and other

minorities altered California��s

social structure in the 1930s, destabilizing its political system in the 1940s

and pushing the state towards the right of the political spectrum. Mobilizing

for war, the formerly agricultural California

industrialized to accommodate its new defense industry. The existing film

industry in Hollywood created

anti-Nazi propaganda and abandoned its isolationist message. The new California

was a product of the war and ��a direct creation of the national will,�� but at

the same time it helped shape the war and the postwar climate.1

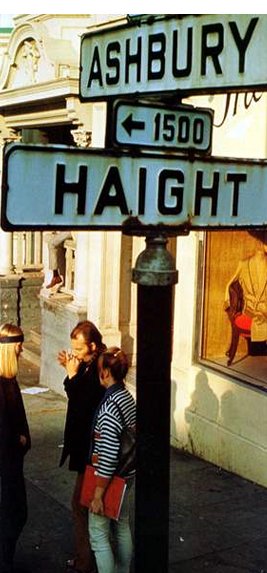

Starr begins his analysis in 1940,

when isolationism was still strong in California,

and people partied and had fun as a way to ignore ugly realities. While the

Depression was by no means over, Californians enjoyed new luxuries and immersed

themselves in escapist radio programs and movies, loath to recognize signs of

escalation such as the Selective Service Act, the first peacetime draft.

Ambivalent towards politics, they accepted Franklin D. Roosevelt as president

but turned away from their Democratic governor Culbert

Olson, perhaps as a way of ��resisting Roosevelt��s

interventionism.�� 2 They were by no means ignorant of their danger,

however, and when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor,

the majority of the population reacted with fear and instant paranoia of a

mainland invasion. Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War led to the

Associated Anti-Japanese Leagues, Theodore Roosevelt��s Gentleman��s Agreement,

and the segregation of Japanese children in Californian schools in the early

twentieth century, decades before internment. California��s

blatant racism had been brewing for decades and erupted when Japanese Americans

had finally established themselves as normal, hardworking Americans who were an

important economic force.

After Californians accepted the

necessity of war, they became major contributors to the war effort. Californian

Major General George Patton trained soldiers for combat in North

Africa at the Desert Training

Center in Southern

California, Nevada,

and Arizona. The Navy and Marines

established their presence in San Diego,

Long Beach, and San

Francisco, and numerous training centers, bases, and

ports of embarkation shuttled servicemen to war in the Pacific. Due to the

young age of many soldiers, military life inevitably joined with college life,

and soldiers in the Bay Area were able to attend co-ed dances with students

from UC Berkeley or find other entertainment in

lively San Francisco. For all the

partying, servicemen realized that they might not return from war, and this led

to the Los Angeles Zoot Suit Riots in June 1943,

where sailors attacked young Mexican American men, perhaps out of jealously of

the self-expression that men free from military service could indulge in. The

Mexican government, an ally to the U.S., instantly protested, and Eleanor

Roosevelt compared the ��race riot against Mexicans�� to the ��riots against

blacks in Detroit,�� but strangely enough, no one was hurt in the Zoot Suit Riots which had a carnival-like atmostphere.3 After the removal of Japanese

Americans along the Pacific Coast to inland internment camps by Executive Order

9102, Californians who often linked whiteness to loyalty naturally targeted

Hispanics, but they also discriminated against blacks who moved for employment

in the defense industries. Ironically, discrimination occurred to a lesser

extent within the military, and Mexican Americans and Japanese Americans were

both highly decorated ethnic groups, greatly honored for their service to a

nation that rejected them. With so many men overseas, defense industries turned

to women for labor out of necessity, providing conveniences such as day-cares

and cafeterias and introducing ergonomics to adapt machinery to women��s

physical limits. As many young women moved to the Coast hoping for a shot at Hollywood,

aviation became the most glamorous defense industry, highlighted by the fact

that Charles Lindbergh��s Spirit of Saint

Louis was built in San Diego.

Before the war ended, developments already pointed at a prosperous postwar

environment, and Los Angeles began

meeting the housing shortage with middle-class dwellings. The American dream of

a car and a home in the suburbs seemed to become a reality in California,

now industrialized and independent of the East Coast.

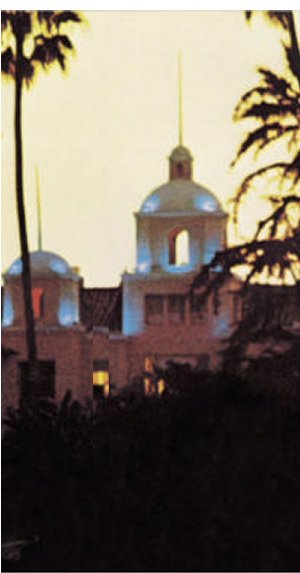

Starr makes constant reference to Hollywood,

and he devotes chapter six to the role of stars and the film industry in the

war. Bob Hope became Hollywood��s

main spokesman for the war, and Bette Davis organized the Hollywood Canteen

where servicemen could meet actors and actresses. Although the rich and famous

tried to throw themselves one hundred percent behind the war effort, the public

became disenchanted with propaganda films by 1944, including Hollywood Canteen where stars

condescended to mingle with soldiers, and resented the war of privilege where

actors and producers automatically received safe officer positions. In total

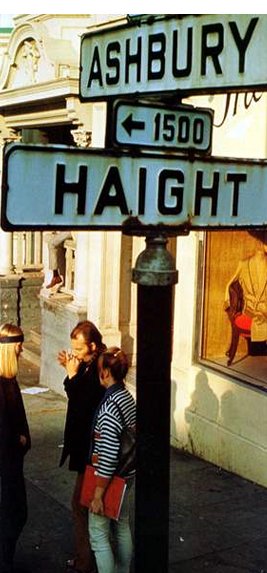

26,000 Californians died in the war, but hundreds of thousands of veterans

settled in California, including

those who fell in love with the freewheeling atmosphere of the hospitable Bay

Area. The Servicemen��s Readjustment Act of 1944, better known as the GI Bill of

Rights, gave health care, home loans, unemployment insurance, education, and

more to veterans so that in 1946, more than half of the students at USC were veterans, and 43% at UCLA in 1947 were as well.4 Many veterans settled comfortably in the

suburbs, buying simple massed-produced houses, but behind the veil of

contentment, people were still uneasy about the rise in youth delinquency due

to the absence of parents and the rise of organized crime. One Elizabeth Short,

nicknamed the Black Dahlia after a dark film by Raymond Chandler, was found

mutilated in LA in 1947, just one of the many murders that the public became

immune to. Starr uses her case in chapter eight to emphasize the anonymity and

cruelty of life in the big cities, where mobsters became respected figures and

intellectuals lamented the fakeness and grimness of life.

Representative of the

contradictions in California,

three-term governor Earl Warren was a family man who showed off his photogenic

Kennedy-like family, but at the same time he was a hardened prosecutor and

crime fighter. Warren was a

professed Republican, but due to the practice of cross-filing where a candidate

can enter both party primaries regardless of his own political beliefs, in a

way he was a unified Party of One. Using mass media to widen his campaigns, he

reached individuals in a nonpartisan way, attracting minorities and unions,

imitating Roosevelt��s New Deal, and creating his own

brand of progressivism. In chapter ten, Starr discusses conservative

conservatives involved in the anti-Communist crusade. The House Un-American

Activities Committee attacked Hollywood

for its Communist affiliations, and the Tenney

Committee led by Senator John Tenney accused the UC system of being too sympathetic to Communism. Richard

Nixon of Southern California brought down the ��pink

lady�� Helen Gahagan Douglas. The Communist Party in

California was very open and produced optimistic literature anticipating the

civil rights movement of the 1960s, but the state as a whole veered sharply to

the right in light of the Cold War, though not one of the seven hundred

individuals blacklisted by Tenney was so much as

indicted because he carelessly named prominent Californians and made

unreasonable accusations. 5 Starr concludes the eleventh and final

chapter on a hopeful note by mentioning Warren

again, who was appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court by President Dwight

D. Eisenhower. One of the most liberal Justices in history, Warren

presided over Brown v. Board of Education

in 1954 and Miranda v. Arizona in

1966, causing Republican Eisenhower to regret the appointment. However, Warren

helped reverse the illogical hysteria in California

and the nation that accompanied the end of World War II which he at one time

had contributed to.

Though he often appears to digress,

Starr��s tangents actually relate closely to his thesis that not only was California

changed by the war, it also shaped the war and people��s perception of the war.

Starr analyzes California in

relation to the world and doesn��t isolate events from their time period in an

effort to show cause-and-effect relationships. He mentions California��s

effects on foreign policy, such as the embarrassment the state brought on the

nation by its racism and its role in escalating the war, claiming that ��the

White California crusade had poisoned the well between Japan

and the United States��

and perhaps led to Pearl Harbor. 6 Listing

important figures from California

such as Patton, Hearst, Nixon, and Warren and many others associated with Hollywood,

Starr backs up his claim that the Golden

State��s influence on the entire

nation was proportional to its great size. Ultimately, he shows how California

reflected the American dream despite some of its less memorable aspects.

Throughout the book, Starr makes it

clear that he is a New Left historian, concerned with racism, women��s rights,

and the repressiveness of anti-Communist sentiment. Born 1940 in San

Francisco, Starr was California State Librarian and is

currently Professor of History at USC, partially

explaining his preoccupation with developments in colleges. He served as a

lieutenant in West Germany

around the time of the Vietnam War and has authored six books in his series, Americans and the California Dream,

dealing with California in

different time periods from 1850 to 1950. With clear knowledge of Californian

history, he often makes reference to events outside the time range of World War

II that still contribute to his narrative. Very sympathetic to the plight of

minorities, Starr attempts to be impartial but does evaluate some events from

his personal point of view, calling the deportation of Japanese Americans ��one

of the most egregious violations of civil rights in American history.�� 7 He

mildly censures HUAC and government reactions to mass

hysteria, sharing the disillusionment of most Americans today.

Embattled Dreams received

relatively favorable reviews from critics including Benjamin Schwarz. Schwarz

notes that Starr ��covers such disparate subjects�� and ��stresses continuities,

rather than abrupt change.�� 8 He congratulates Starr��s understanding

of The Folks and his emphasis on Earl Warren, but he feels that the absence of

any mention of Billy Graham��s influence on religion in California

is inexcusable. Eric Schine delivers a glowing review

emphasizing Starr��s summary of the social revolution in California.

Though he feels that ��Starr sometimes overindulges�� with detailed anecdotes,

��such brief lapses are a small price to pay�� since Starr more than adequately

analyzes California��s role in the

American experience. 9 Though each reviewer finds a small flaw in

the book, both feel that it is a worthwhile read that accurately sums up

Californian influence during World War II.

Starr is quite the master at

blowing up a small detail so that it represents an entire aspect of Californian

culture. Each of his chapters takes its name from an anecdote; chapter nine

��Honey Bear,�� for example, is the nickname of Warren��s

youngest daughter and as a chapter name refers to Warren��s

use of his family in the media as ��the very emblem and spirit of California.��

10 Although such connections may be a bit of a stretch, the chapter

titles reflect the content and anecdotes in those chapters and show how Starr

can build an argument from the most insignificant of events. As Schine notices, these little stories sometimes become too

long and beside the point, but the use of cultural references and descriptions

of individuals lend credibility to Starr��s thesis and add a dash of color to a

history book, though several biographies could have been made more concise.

Starr could have made greater reference to World War II and put less emphasis

on Hollywood, but as the title

suggests, he analyzes the entire decade and looks at history as an ongoing

process, where to ignore one point of view is to lose focus of the subject.

Starr��s emphasis is the pervasive

influence of California on the

rest of the nation, and he makes short shrift of the East Coast��s effect on the

West, only saying that the war made California

industrialized and independent, implying that agricultural California

had depended on the East for manufactured goods. The only ways the East has an

impact of California, according to Starr, is through the national government in

Washington, D.C. Franklin Roosevelt issued several Executive Orders for

Japanese internment and fair employment practices, and in 1950 the California

National Guard of ten thousand men was ��called to active duty and

nationalized�� for ��the global

conflict with Communism.�� 11 HUAC also

affected California in its

persecution of stars such as the Hollywood Ten and the pressure it placed on

the UC Regents to create a loyalty oath for its

faculty. The migration of Okies and blacks to California

from the East and Midwest for work in the defense

industries changed the social and economic structure prior to World War II. In

a way, the East thus made California

distinctive from the rest of the country by creating a fluid society of

vagrants, and the return of veterans increased the population and worsened the

housing and transportation crises which still exist today. Before the war,

Californians would have been content staying in agriculture, but

industrialization and the social revolution that accompanied it changed

people��s aspirations and expectations.

As the mainland state most

vulnerable to Japanese attack, California

served as the largest homeland military base for the U.S.

In February 1942 ��Commander [Kozo] Nishino and his submarine were capable

of�Kthe shelling, strafing, and torpedoing of [the] American city�� Santa Barbara.12 California was certainly in the most

danger, and its large population of Japanese Americans heightened anti-Japanese

and generally xenophobic sentiment that affected foreign policy and hurt the

reputation of the United States in the eyes of its allies. The Sunshine

State produced Nixon, one of the

leaders in the anti-Communist movement, but at the same time it was a favorite

target of HUAC. Physically protecting the nation by

building aircrafts, ships, and weapons and training soldiers, California

also provided a morale boost by being the nation��s propaganda center. No other

state had such a great part in determining national culture and the outcome of

the war, and no other state so perfectly embodied the American dream.

Events

in the East had some effect on the West, but ultimately lifestyle changes in California

created disproportionate changes for the nation as a whole. World War II was

perhaps ��an intensification of prior developments rather than a beginning��: the

Great Depression brought the Okies to California and

the war merely led to their assimilation, Californians generally already hated

the Japanese as inassimilable economic competitors and the war was an excuse to

remove a longtime enemy. 13 The defense industry modernized

California and altered the nature of its economy and its relationship with the

East, and the people it attracted disrupted the more liberal political

institutions, allowing the rise of zealous opponents to Communism just as

Governor Warren was introducing socialist policies. Hollywood came to be a

channel of expression for Americans and a representative for the war. The war

changed California beyond

recognition, but one role it could not change was that of the final destination

of Manifest Destiny, the promised land where Americans

had the best chance of finding the perfect, idyllic life.

1. Starr, Kevin. Embattled Dreams, California

in War and Peace 1940 �V 1950. New York:

Oxford University

Press, 2002. ix.

2. Starr, Kevin. 24.

3. Starr, Kevin. 111.

4. Starr, Kevin. 191.

5. Starr, Kevin. 307

6. Starr, Kevin. 37.

7. Starr, Kevin. 37.

8. Schwarz, Benjamin. ��California Transformed.�� Atlantic Monthly May 2002. 01 June 2008

< http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200205/schwarz>.

9. Schine,

Eric. ��When California Came of Age.�� BusinessWeek 13 May

2002. 01

June 2008

<http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/02_19/b3782037.htm>.

10. Starr, Kevin. 241.

11. Starr, Kevin. 308-309.

12. Starr, Kevin. 35.

13. Starr, Kevin. vii.